A Flight of Fancy

A warm spring day, Friday night, the sun just beginning to set behind Kelburn hill, hiding its warmth, and throwing the last of its light onto the clouds above. A painting emerges - hazy blues and whites transformed into the richest of scarlets, succulent tangerines and moody, deep sapphires.

Indulging in the view, three stories up, my daydream vanishes. I’m snapped back into reality by other, more urgent senes. The heavy rumble and roar of a diesel bus puts a furrow in my brow. I think I can smell the exhaust. Vehicles jostle for position in the car park below, the frustration of tight spaces and parallel parks, and stop, go, stop, wafts up. The clinking of glasses, hearty laughter, and friends reuniting from the bar across the way adds to the cacophony.

But I can’t hear any of it. I only have ears for one, the coughing, creaking, buzzing, interspersed every so often with delightfully tuneful notes of a Tūī, making itself at home, in a tree, amongst the patrons of the bar. Right in the heart of Wellington city.

As their calls ring out across the city, a recent report by Wellington City Council tells the true tale of the successful return native wildlife across the region. 85%, 200%, 260%. Increases recorded in bird call counts from around the region over the last decade. Tūī, kererū, and kākā thriving. Titipounamu/riflemen, small as they are, have been spotted in the wild in Wellington for the first time in a century. I can believe my eyes and ears.

It always feels like a treat when I see our hear from our feathered taonga. I hadn’t always been a fan. Growing up on a quite Hawkes Bay lifestyle block, I was used to the sounds of nature. But aside from the occasional swooshing of a kererū in flight, or the flitting of a rare pīwakawaka snagging up some tasty bugs, it was the sounds of wind in the trees, of the ocean, or the quite baaing of lambs in the distance. The not so quiet cows - bellowing in the evening. As a family, we always had cat (or two), and being on a lifestyle block, the were very much outdoor cats. I couldn’t image my childhood without them. When they eventually all passed, and were very much not replaced, visiting home I couldn’t help notice just how effective our cute furry felines had been at keeping our feathered friends at bay. I like to think the birds were just clever enough to stay away.

Lets leave it at that.

Nature back home

Nature back home

With plenty of reserves and national parks up and down the country, I find it easy to be inspired by our native wildlife, rugged landscapes, and rich dense forests. Local to Wellington, it's a quick trip up to Te Māra a Tāne Zealandia, located just before the suburb of Karori.

Stepping through the imposing predator free fence gate, into the 500+ acre sanctuary, I feel a weight lift off my shoulders. I open my ears, and can hear friends calling in the distance. It’s not the first time I’ve wandered through Zealandia, and certainly won’t be the last. Where else can you sit down for a breather, and have takahē casually stroll by, as if it’s doing the rounds, making sure everyones ok and answering any burning questions you might have?

This visit, I’m feeling energetic. I resolve to walk all the way to the top of valley. The further I go, the quieter it gets, and the louder it gets. Quite conversations about the wind and the weather are replaced with the wind and the weather, and familiar voices begin to appear amongst the dense bush. Flocks of pōpokotea/whiteheads happily chitter across the winding path. The sudden laughter of a tīeke/saddleback stops me in my tracks for minutes. Too quick to snap a picture, but the memory remains, more rich and textured than any collection of digital bits.

Entirely enclosed by a predator free fence, Te Māra a Tāne Zealandia was crucial catalyst to the boom in our feathered taongas return to the Wellington region. With no cute furry predators, nor rats or slinking mustelids (stoats and ferrets), the birds have had free roam of the massive sanctuary, nestled within the inner city suburbs of Karori, Brooklyn, and Highbury.

And roam and breed they did, the sanctuary providing a halo effect for the rest of region. The success of the sanctuary is undeniable, and booming bird populations spread their wings across the south of the North Island. Efforts like Zealandia are heavily supported by predator free movements across the Wellington region. Networks of traps, numbering in the thousands keep predator numbers low for any travelling birds looking to establish themselves further afield. And then there’s the people. Predator Free Wellington coordinates with 58 community groups across the region to maintain, and monitor some of these trap networks.

A few weekends later, my partner and I decided to wander along the Wellington water front. Before we left, I applied my favourite cologne for the lengthy stroll we intended to take, the smell of summer. Lathered in sunscreen we made our way around the waterfront, and I couldn’t help but find my thoughts returning to the birds, the birds.

Reading the councils report, what struck me was the human effort involved. Conservation appears to be a stubbornly manual task. The stunning increase in native bird numbers is recorded by a combination of citizen scientists submitting their own first hand accounts, and professional bird call observers, from 100 randomly selected locations in parks and reserves across the region. They are at pains to state the difficultly of identifying individual birds, and the steps they take to ensure their reports are accurate. I wondered what the future of monitoring would look like, 20 or 30 years from now.

I had heard (you’ll see why this is funny) that there are people who are interested in birds, and how their abundance is monitored. I found my way to the website of AviaNZ. A team using bioacoustics as a way to measure the abundance of individual birds.

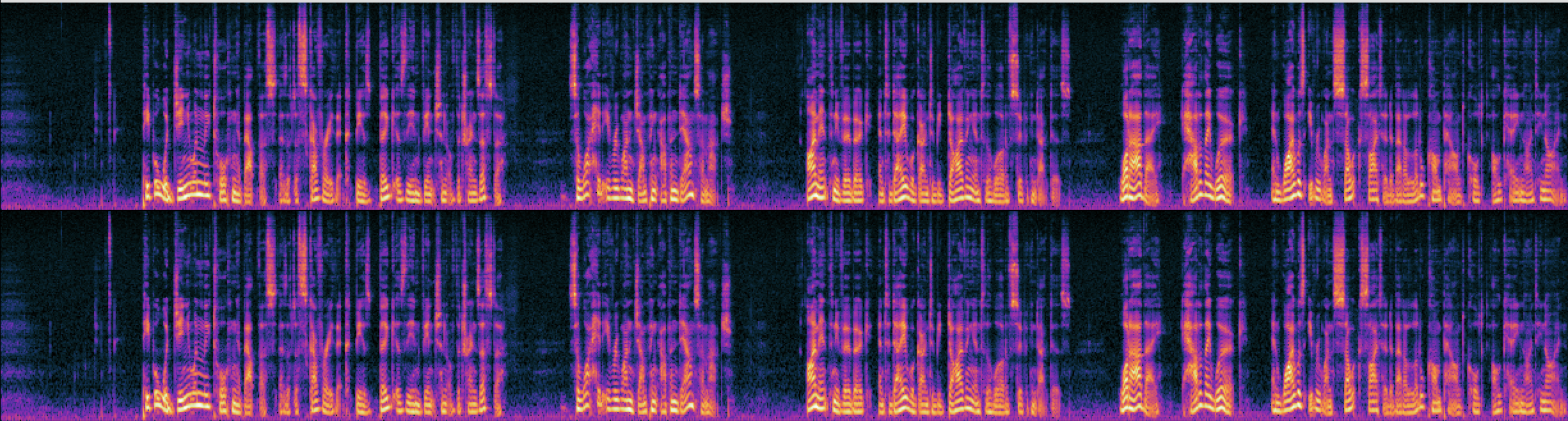

Professor Steven Marsland tells me that he’s always been interested in birds, and he’d had an idea in his head for a while, before teaming up with biologists, ecologist, and fellow mathematicians and data scientists to realise his idea. They have created a program that, once trained, can recognise species specific noises, for example my creaking, buzzing, singing tūī friend. An automated way to determine the abundance of calls that a microphone in a reserve might pick up. He tells me they’ve been working with kiwi, attaching microphones to them so that they can determine how often these birds actually call. So called ‘ground truth’ data, to identify individuals. They’d like to one day do this with other species. I ask about the future of this technology. At the moment, you have to manually feed audio files into the program, and it only works for one species at a time. Maybe one day the software will run hands free, on a solar powered device, in the field, automatically identifying all the species it’s learnt to. He says that’s still a long way off.

A spectrogram of my call (voice)

A spectrogram of my call (voice)

Returning from our walk, we’d worked up quite a thirst, and as the sun began creeping behind the hill, we found ourselves quenching our thirst in a quiet garden bar, just off Courtenay Place. Well deserved, I thought, as I appreciated the shade provided by the kōwhai trees around us, their flowers reaching downward, swaying in the gentle breeze as if they’d had one too many. Cough, creak, buzz! With a dramatic swoosh and dive there it was, just above, darting amongst the flowers, its beak covered in pollen.

Quietly laughing to myself, I listened to its noisy chatter, wondering if from that I could tell if it were my friend from across the road.

Maybe one day, we might not need to wonder.